Parenting Anxiety and the Antidote of Camp

Not long ago, the U.S. Surgeon General declared parental stress a public health crisis. That statement landed with force because it put language to something many families already feel every day. Parenting today often feels heavier than it should. The stakes feel higher. The margin for error feels smaller. And the constant flow of information about what could go wrong can quietly convince even thoughtful, capable parents that worry is not only normal, but necessary.

Dr. Meredith Elkins, a clinical psychologist and author of Parenting Anxiety: Breaking the Cycle of Worry and Raising Resilient Kids, has spent years studying how this culture of anxiety takes hold. One of her most important findings is also one of the most counterintuitive. The very strategies parents use to reduce anxiety in their children often end up strengthening it.

Elkins explains that anxiety is not a sign that something is broken. Fear, sadness, and uncertainty are normal human emotions, especially for children who are learning how the world works. Problems arise when those emotions are treated as emergencies. When parents rush to eliminate discomfort, avoid challenge, or immediately fix distress, children receive an unintended message: these feelings are dangerous, and you cannot handle them on your own.

A distinction we talk about often at North Star is the difference between being unsafe and being uncomfortable. Unsafe situations require intervention. Discomfort, on the other hand, is often where growth begins. Anxiety blurs that line for both kids and parents. When everything feels dangerous, it becomes tempting to remove challenge altogether. Elkins’ research reminds us that learning to tolerate discomfort is not reckless. It is essential.

Over time, children need opportunities to practice sitting with uncertainty, working through nerves, and discovering that anxiety often fades when they stay with it. Research consistently shows that avoidance is one of the strongest drivers of long-term anxiety. The more we help children avoid what makes them uncomfortable, the less capable they feel when discomfort inevitably returns.

Elkins encourages what she calls a “love and limits” approach. Love means empathy, validation, and connection. It sounds like, “I know this feels hard,” or “It makes sense that you’re nervous.” Limits mean not removing the challenge simply because it is uncomfortable. It sounds like, “I believe you can handle this,” and then allowing the child to try. This balance teaches children that feelings are real, but not dangerous, and that they are capable even when things feel hard.

This philosophy is deeply woven into the way we think about growth at camp.

One clear example is our progressive tripping program. Each summer, the challenges build. What might start as a short overnight trip for a younger camper gradually becomes longer, more complex, and more demanding as they grow. Canoe carries get heavier. Routes get longer. Responsibility shifts from counselor-led to camper-led. It is common for campers to feel nervous before these trips. Many doubt whether they can do it. And almost without exception, they come back standing a little taller, proud not because it was easy, but because it wasn’t.

The same is true across our daily program. For some campers, the anxiety shows up the first time they try waterskiing, when the boat pulls forward and they have to decide whether to hold on. For others, it is climbing the wall, stepping off the platform onto the zip line, riding a horse for the first time, or walking into an activity where they do not yet feel skilled. These moments are not forced. They are invited, supported, and encouraged. Counselors are trained to recognize fear, normalize it, and then help campers take the next small step forward.

Our objective-based programming plays a quiet but important role here as well. Campers are not competing against one another so much as they are competing against themselves. Clear benchmarks give structure to effort and turn vague fear into achievable goals. Progress becomes visible. Mastery replaces avoidance. Each level passed becomes evidence that effort matters and that improvement is possible.

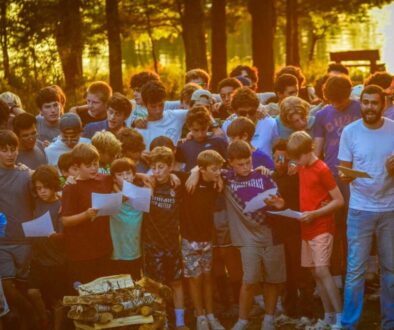

At the end of each week, cabin campfires provide space to reflect and set goals. Campers talk about what felt hard, what they are proud of, and what they want to try next. Naming challenges out loud, in a group that listens, helps boys understand that anxiety is not something to hide. It is something to work through. These conversations also reinforce that growth is not accidental. It comes from intention, persistence, and support.

Another critical finding in Elkins’ work is the role of parental modeling. Children learn how to interpret stress by watching the adults around them. When parents respond to separation, uncertainty, or challenge with visible panic or excessive reassurance, children absorb the belief that something is wrong. When parents respond with calm confidence, even while acknowledging their own feelings, children learn that discomfort is manageable.

This is where overnight camp becomes just as much a growth experience for parents as it is for campers. Choosing not to intervene immediately. Resisting the urge to rescue after a hard letter home. Trusting that support exists even when you are not the one providing it. Elkins’ research makes clear that this is not abandonment. It is confidence in your child’s capacity. It is how the cycle of anxiety is interrupted rather than reinforced.

Camp is not an escape from the real world. It is preparation for it. It gives children a place to practice independence while the stakes are still low and the support is still close. It allows parents to step back in a way that feels intentional rather than negligent. And it reminds families that growth often comes through discomfort, not around it.

If this topic resonates, I strongly recommend watching Dr. Elkins’ recent talk hosted by the Family Action Network (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9WJJu0YR_M), as well as reading her book,

Parenting Anxiety: Breaking the Cycle of Worry and Raising Resilient Kids (https://www.amazon.com/Parenting-Anxiety-Breaking-Raising-Resilient/dp/0593798813). Her work offers reassurance grounded in research and compassion, not fear.

Parenting will always involve worry. That part does not disappear. What can change is how much power that worry holds. When we help children understand the difference between unsafe and uncomfortable, and when we give them repeated chances to face challenge with support, we give them something lasting. Confidence. Resilience. And the belief that they can handle what comes next.

Carry On,

Andy